FROM WISŁOUJŚCIE TO BRZEŹNO: THE FIRST GDAŃSK LIGHTHOUSE

From the fourteenth century Gdańsk gained increasingly in significance and became one of the most important trading centres in this part of Europe, thanks to its advantageous situation on the Baltic. To reinforce this position, care had to be taken over separation of the vessels navigating the entire bay and safe entrance to the port had to be ensured. This function was fulfilled by lighthouses. The first in Gdańsk was one at built at Wisłoujście in 1482. It was housed in a tower of the type known as a blockhouse which had been built earlier by the Teutonic Knights. It was 18.3 metres in height and the fire that was kindled on its platform was visible at a distance of up to about twenty kilometres. In the course of the following decades new fortifications were built around it, which together formed the Wisłoujście Fortress. After the destruction of the lighthouse tower in 1577 by the artillery of King Stefan Batory, it was quickly rebuilt. Its height was increased and the top was crowned with a cupola. At the same time a new source of light was introduced in the form of four olive oil lamps with reflectors of polished brass. In addition there were steel masts beside the tower with metal vessels in which to burn olive oil. The lighthouse at Wisłoujście was in operation until 1758, when it was closed.

Over the years the water of the Vistula had deposited at its mouth a large amount of sand, carried there by the current. This formed sandbanks and bars (and finally the whole Westerplatte peninsula) and caused changes in the current of the river, thus significantly distancing the entrance to the port from the lighthouse. At the same time technological progress meant that ships of ever greater tonnage and draught were beginning to come into port at Gdańsk, and for these the shallows posed a serious danger. Many of the captains complained to the merchants of the state of the river and suggested that a new lighthouse be built at a different site nearer the sea. The city authorities therefore decided on a change of position for the navigational light.

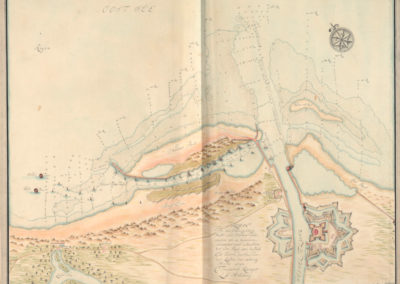

After long deliberations the city council, with the agreement of the Association of Sea Merchants (who in turn had consulted ships’ captains, both local and foreign) stated that one lighthouse did not fundamentally change the situation, as it would only indicate to the sailors the position of the roads. It was decided that the new navigational signal would be made up of two lights, a higher and a lower, set 75 metres apart. The best location for this was the district then known as Brösen, now Brzeźno. The two lighthouses would coincide so that they would form what might be termed a directional lighthouse complex to show ships under sail the exact line to the port entrance. The changes were preceded by a leaflet published on 3rd August 1758, in which it was generally announced that for “the sake of the sea-trading merchants” the light at Wisłoujście would no longer be lit. Instead of it, from 24th September to 24th March annually, coals would be lit at two new lighthouses.

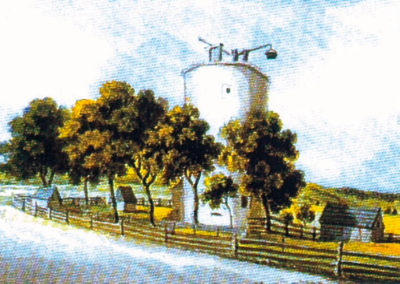

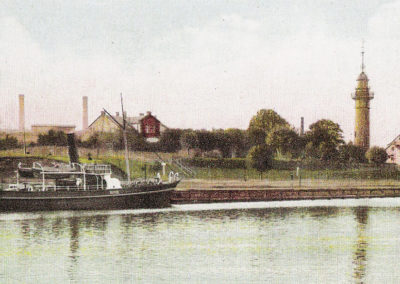

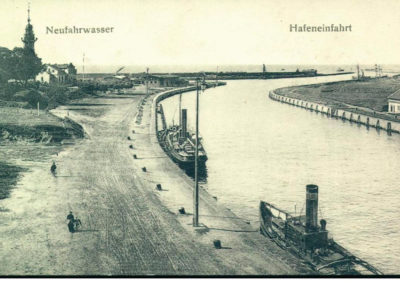

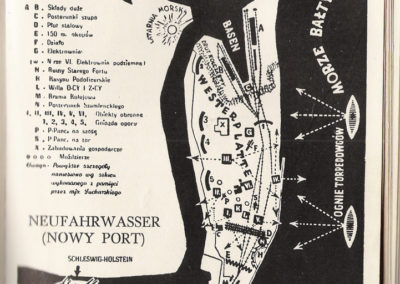

And it was indeed on the 24th September 1758 that the two new lighthouses came into service. The lower of these was a crane lighthouse. Coals were lit in a suspended basket known as a Vulcan’s pan, which was housed on a circular brick platform. The taller lighthouse was a walled tower of 20 metres in height and 10 metres in diameter, at the top of which coals were also lit in an iron basket. The lighthouse keeper lived on the ground floor and in the basement fuel was stored. The two towers were situated on Bliesenstraße (today’s ulica Blizowej), close to the railway station of Nowy Port (then Neufahrwasser), on the left bank of the harbour channel about 1,500 metres from the head of the northern breakwater and 450 metres to the south-east of the lighthouse that now exists. The tower was painted with white oil paint.

In 1817 the rock coal, which in a gentle breeze gave out an insufficiently bright light but in a strong wind was used up too quickly, was replaced by wax candles of over five centimetres in diameter. This probably occurred when a round glazed cabin, the lantern room, was built on the flat top of the taller lighthouse. However, because the light obtained in this way was still decidedly too weak and its measurement difficult, the authorities of the City of Gdańsk (Danzig) proposed the introduction of gaslight, mounting three gas burners on each of two platforms. These were what are known as Argand lamps and had parabolic reflectors of 53 centimetres in diameter and a focal length of 23 centimetres. The gas used for light was obtained from rock coals in its own gasworks. In 1825 the number of Argand lamps in the lighthouse was increased to five, but 35 years later, owing to the high maintenance costs, the gas burners were exchanged for seven lamps powered by oilseed rape oil, which in turn gave way to petroleum ten years later. The lamps were distributed along two arcs suspended one over the other and had a range of 14.5 nautical miles using a white light. Their height above sea level was 23.5 metres, with the tower height totalling 21.7 metres

In 1887 the newspapers reported in a sensational manner attempts to install electric lighting in the lighthouse. A 15-amp electric lamp on direct current was installed in the lantern at this time. The energy for this was produced by a generator set in motion by a steam engine set up in the neighbouring lighthouse. The first attempts at an electrically powered lighthouse on the Baltic indeed proved satisfactory, although for the light to be seen beyond the Hel Sandspit it was necessary to place it at least a few metres higher.

NOWY PORT AND THE NEW LIGHTHOUSE

In the nineteenth century the land to the south of the Gdańsk harbour channel began to be settled by those who were working on the port that was then being built. This area and its port were called Neufahrwasser (Nowy Port). By the second half of the nineteenth century it had become an important place for the trans-shipment of cargo and from 1867 had a railway link with Gdańsk (Danzig). The land to the north of the lighthouse described above formed the port area. From at least 1849 a piloting station was located on Wzgórze Pilotów (then Lotsenberg), which lay to the north west of the two lighthouses. This issued storm warning signals and in July 1876 a time ball station came into use. The necessity of having a higher light and of installing a stronger lens and the fact the taller lighthouse had been in use for over 130 years led to the decision by the Gdańsk (Danzig) authorities to build a new one. In a report by Adolf von Heppe the District President of the city, we read that the old white light at Neufahrwasser ceased to meet current requirements and that it would be necessary to place it at least seven metres above mean sea level so that it would be visible to ships passing by Hel. For this reason too and in consideration of the many improvements that had been suggested, the Ministry of Public Works decided to build a new tower on Lotensberg, which would be equipped with an electric arc lamp.

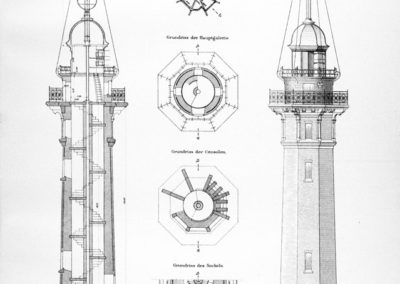

This was finished on 31st October 1893. It was mounted on a four-metre thick foundation with a diameter of 8.5 metres. Crushed rock combined with concrete was used for the construction of this, with additional reinforcement from piles driven into the ground. The lighthouse was built in what was then the prevailing style of “Renaissance Gdańsk,” with red bricks, baked at a high temperature. The lighthouse plinth, elements of the bricked balconies and some decorative tiles were made of white (now dark grey) sandstone. The new lighthouse for Gdańsk (Danzig) was over seven metres taller than its predecessor. The massive granite base of the tower rises nine metres above sea level. The octagonal tower, complete with a gallery and copper dome reached a height of 27.3 metres. In its silhouette a similarity has been discerned between the lighthouse and the most attractive representative of this type of building, the lighthouse on Lake Erie at Cleveland, Ohio, now no longer in existence.

The internal steps of the building were made of granite. Iron ladders led (and still lead) to the lantern room of cast iron plates. The original source of light was an electric arc lamp, previously used in the now decommissioned lighthouse. The cost of the new lighthouse totalled 156,000 marks. Next to it a machine-room and a lightkeeper’s house were built.

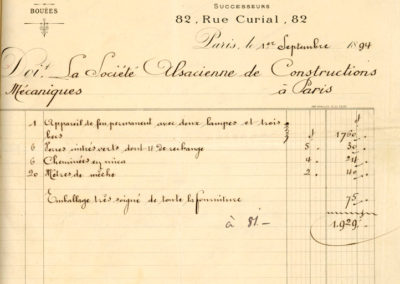

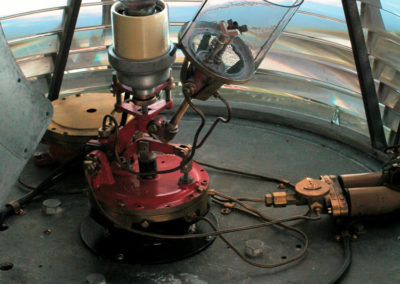

At the top of the building a time ball was placed. The equipment had been transferred from the wooden tower, in which it had operated since 1876. At twelve o’clock noon each day, at a telegraphically transmitted signal from the Berlin Royal Observatory, the 70-kilogram ball slid down the mast erected on the lantern room roof. The fall of the ball was a signal to the navigators of ships moored nearby, and according to this they were able to adjust their chronometers precisely. On this precision depended the accuracy with which the geographical longitude of the ship’s position was specified when out on the open sea. After the new lighthouse had been built, its predecessor, the higher of the two lighthouses, turned out to be redundant, and in 1896 it was dismantled. The new white lamp brought into use in the new lighthouse reached a strength of between 20 and 28 amperes. Its strong light was visible even in mist and in a murky atmosphere, while in good weather conditions it could be seen as far away as the Hel Peninsula. The optical apparatus was made by the well-known Paris firm of Barbier and Fenestre under the patent of the French physicist Augustine Fresnel. Because of the installation of the time ball over the cupola, the optical and lighting equipment was not placed centrally but moved over a meter from the vertical axis of the tower to avoid damage to it from the falling ball.

The specifications of the light emitted from the lighthouse were changed several times, as the steady light which the lighthouse gave out at first was difficult to pick out at night against the background of other shining points in Gdańsk and Nowy Port. In particular, ships under sail that tacked eastwards from the latter in a west wind had difficulty in fixing the position of the light properly in order to confirm how far they were from land and thus risked running aground on a shoal. To avoid confusion with fixed port lights the German Shipping Association saw to it that a flashing light was put in the lighthouse. Finally it was decided to make use of new equipment commissioned from the firm of Julius Pintsch in Berlin. On 20th October 1911 a system was fitted by which the lighthouse shone for one second and was dark for the next four, after which the cycle was repeated. From then on, the ships’ captains knew that only one lighthouse in the Baltic region emitted this distinctive signal. The angle of illumination of the lighthouse was 180 degrees and this was divided into five sectors. In the middle sector the light shone white while on either side it was green and orange. The middle sector achieved the maximum range of 20 nautical miles.

The lighthouse at Nowy Port (Neufahrwasser) did not only show ships the entrance to the port at Gdańsk (Danzig). The vessels under sail there also made use of the time ball and other functions of the building, as it was also a station for the harbour pilots, who were posted in a space with a balcony under the lantern. Equipped with binoculars they observed nearby ships through a window or from the balcony. When one of the ships hoisted the appropriate flag as a signal, a pilot would run down the stairs to the nearby moorings, sit down in a boat and row in the direction of the vessel. Next he would go onto the captain’s bridge and guide the ship through the port channel to the city quay. At no port in the world is the captain allowed to steer the ship into port by himself.

No unauthorised person was able to enter the lighthouse. In 1894 the Commandant General issued a secret order by which visiting the lighthouse was forbidden. Civilians and military personnel alike had to obtain the signature of the District President when applying for permission to view the building. During those years therefore few people were able to admire the beauty of the impressive panorama the opened out from the top of the lighthouse and extended over the entire Bay of Gdańsk to Sopot and Gdynia (then a village and only from the early twentieth century an ever more dynamically developing city), to the Hel Peninsula and to the Vistula Sandspit. The illustrious scholar and adventurer and traveller Baron Alexander von Humboldt (1767–1835) marvelled at the view then (probably already from the higher lighthouse), calling the Bay of Gdańsk (Danzig) one of the three most beautiful coastlines in Europe, beside the Golden Horn in Turkey and the Gulf of Trieste on the Adriatic.

During the First World War, to be precise in January 1915, at the behest of the imperial navy a top lamp was installed on the tower and a small reflector in the gallery. In the course of time the time ball, never the height of modernity, became an anachronism with the invention of the radio by Guglielmo Marconi. When a storm tore off the mechanism in Gdańsk in 1929 it was not repaired. During the interwar period the main source of light for the lighthouse was a bulb fitted into optical equipment and a reserve gas light in case of a break in the electricity supply, as was noted in the index of lighthouses and navigational signals published by the Hydrographical Office of the Polish Navy in 1932. Apart from this no greater changes were made at that time.

THE FORTUNES OF WAR

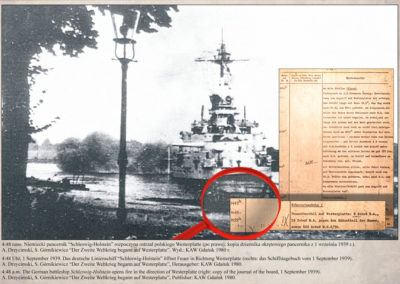

On the night of 31st August to 1st September 1939 the lighthouse was garrisoned by German soldiers with heavy machine guns, who were under orders to fire to hold in check those manning a Polish emplacement at Westerplatte on the other side of the channel. A few hours earlier one of the Polish soldiers had reported that there was an additional large red light on the lighthouse which had not previously been there. According to the commanding officer of the Westerplatte emplacement, Major Henryk Sucharski, this signalled that “the entrance to the port is closed.” As it later turned out, that night the Germans had scuttled barges at the entrance to the port channel to make it impossible for any larger Polish vessel to sail in and torpedo the battleship Schleswig Holstein, which had sailed into port in Gdańsk a week earlier, on the 25th August, “on a courtesy visit.”

All the German armed forces had received the same command from Hitler: open fire at 4.45 am exactly on 1st September. The machine gunners in the lighthouse carried out this command, while the crew of the battleship Schleswig Holstein delayed by a full three minutes and started shelling Westerplatte at 4.48 am. It was those shots from the lighthouse at Gdańsk Nowy Port that in fact began the Second World War, a war that claimed 55 million lives. The lighthouse itself passed into world history. The Polish soldiers, wishing to put an end to the dangerous and exasperating fire from the lighthouse, struck it with a 75mm field gun and, at the second firing of the gun the German machine gun fire was dealt with, the lighthouse tower also being seriously damaged. The Germans immediately rebuilt the façade of the lighthouse, but the traces of this event are still visible to the naked eye, the places damaged by the Polish field gun being distinguishable by their paler brickwork.

1st September 1939

It was actually from the lighthouse at Nowy Port that, on 1st September 1939 at 4.45 am, German soldiers opened fire on the Polish emplacement at Westerplatte, the battleship Schleswig Holstein having delayed, attacked three minutes later. The Polish defenders therefore had first of all to neutralise the dangerous point of gunfire. For this a field gun with a calibre of 75mm was used. When the weapon was rolled by gunners to a station directly opposite the lighthouse, their commanding officer Corporal Eugeniusz Grabowski gave the order. “Take aim: machine guns at the lighthouse window, sight 400, grenade charge normal, short-delay fuse!” The soldiers worked very calmly, “as if at a training ground,” Grabowski recalled afterwards. Bombardier Wincenty Kłys took careful aim and the commanding officer gave the next command “Ready, stand back, fire!” The whole company watched the flight of the missile, but it overshot the lighthouse. The soldiers were dismayed. A shot at a target 410 metres away seemed safe. Corporal Grabowski, however, quickly steadied the nerves of the soldiers, explaining that the miss was an effect of settling the cannon in a new position, and reminded them that in such situations the first shot could not be counted on. A dozen or so seconds later, with the same setting of the sight, the gun was recharged. It was fired and the result was a perfect hit. “It breached the lighthouse under the window. The window grew in size, machine guns fell somewhere or other and brick dust and smoke from the detonation issued from the opening that had been knocked out. The equipment, it turned out, had been in good working order and the gunners well trained.”

A CANNON AT WESTERPLATTE

The history of the 75 mm field gun with which the Polish defenders of Westerplatte answered the fire of the German machine guns from the Nowy Port lighthouse is itself extraordinary. It was one of many thousand three-inch-calibre guns captured by the Prussian army in the victory over the Tsar’s army at Tannenberg in East Prussia in August 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War. As this particular gun had been won by the soldiers of the 128th Gdańsk Infantry Regiment, after the victory parade in September 1914 at Brama Wyżynna (the Upland Gate) of the city it was set up in the courtyard of the barracks in ul. Oliwska in Gdańsk Nowy Port (Danzig NeuFahrwasser) as a symbol of the success and as a great trophy of war.

After Prussia lost in the First World War, their barracks were occupied by English, French and, latterly, Polish troops. As the status of free city obtained by Gdańsk (Danzig) under the Treaty of Versailles did not permit the stationing of any army in its territory, Poland withdrew its army from the city, while, unbeknown to the Germans, transferring their heavy weapons on the vessel Wilia to the other side of the port channel to a Polish outpost at Westerplatte, newly built in 1922. Here Polish troops took to pieces the illegal weaponry, which in keeping with its origin was termed “conventional” and hid it in secret in case various parts of Westerplatte fell under German control. It was not until August 1939 that these armaments were re-assembled and kept ready for action. After the capitulation at Westerplatte on 8th September 1939 the Germans pulled the Polish field gun on board the battleship Schleswig Holstein and transported it to the German Naval Academy at Mürwik near Flensburg. Here, in the courtyard, flanked by two cadets of the Kriegsmarine standing to attention, the Polish gun stood as the greatest trophy of war until April 1945, when, after the entry of the Allies into Flensburg it disappeared and all trace of it has been lost ever since.

POST-WAR FORTUNES

The situation of the lighthouse at Nowy Port when the war ended in 1945 did not look very promising. The lighthouse tower itself was in need of repairs and part of the light apparatus had also been destroyed. The administrative responsibility for the lighthouse, together with other such buildings, was taken over by the Gdynia Maritime Bureau (Urząd Morski w Gdyni). The expectation was that the lighthouse would resume operations four months after taking delivery of necessary equipment that had been ordered from Sweden. The news that it had gone back into service was published in the index of lighthouses and navigational signals published by the Hydrographical Office of the Polish Navy in 1947. This included the information that a light had been installed with a new alternating feature: a two-second flash and a three-second pause. The optical system fitted in the lighthouse, which may still be admired today, was a drum-shaped Fresnel lens made by the Paris firm of Barbier and Fenestre, inside which a lamp bulb was housed in the alternating mechanism. An emergency light was supplied by an acetylene burner. During the post-war period one very significant change occurred to the exterior of the lighthouse. In the nineteen-sixties the mast was removed on which the time ball, now long gone, had once been raised.

The continuing development of the Port of Gdańsk made it essential for a lighthouse to be built in a new place. Exactly ninety years after the Nowy Port Lighthouse had been commissioned its end approached. Just as towards the end of the nineteenth century it had replaced a smaller lighthouse which at that time did not fulfil structural requirements, so it was itself closed on 18th June 1984 with the opening of a larger modern lighthouse in the Port Połnocny (the Northern Port). The monthly publication “The Sea” (Morze) gave the following information at this time: “On the eve of the inauguration of this year’s Sea Days the lighthouse at Nowy Port extinguished its light for what will surely be a long time. The following night a new light could be made out on board a ship sailing on a level with Gdańsk: three flashes of half a second every one and half seconds with half-second intervals. The cycle then begins again.” Should the light fail on the new signalling system, the light of the existing lighthouse could in an emergency be switched on. However, it has never come to that.

A SECOND LIFE FOR THE LIGHTHOUSE

For the next dozen or more years the lighthouse at Nowy Port was closed. No one carried out any repairs, there were rusty railings on the viewing tower and water running through a window pane in the lantern house that had been smashed by a careless seagull. In the roof holes the size of a hat threatened. Year by year rain, snow, ice, wind, sea salt and sulphur completed the work of destruction.

A Pole who had lived in Canada for thirty years, qualified engineer Stefan Jacek Michalak, found the building still in this state towards the end of the nineteen nineties. Michalak considers Gdańsk his home city, having arrived here with his parents from Warsaw on 8th April 1945 as a eighteen-month-old boy, and the sea is in his blood. His grandfather, Szczepan Michalak, was born in 1900 into a family of village wheelwrights in Stary Gród in Greater Poland (Wielkapolska) in the south. At the age of eighteen he emigrated to the large northern German city and port of Kiel, where he lived and worked for the following two decades. He became there a master of artistic carpentry. His great artistic and organisational talents brought him, a Pole among Germans, to the position of director of carpentry at Howaldt-Werft, the largest of the Kiel shipyards. Those were the days when beautifully appointed saloons, captain’s cabins and officers’ messes, executed using wood from rare and exotic trees, were the pride of every shipyard in the world. In 1919, after the rebirth of independent Poland, Szczepan Michalak returned to the country of his birth and worked as an instructor in artistic joinery in the State School of Decorative Arts (later the Higher School of Fine Art), Poznań.

Stefan Jacek Michalak studied electronics at the schools of technology in Gdańsk and Warsaw followed by several years working as an engineer and seaman in Germany, before moving permanently to Canada in 1969. There he lived in Montreal, a beautiful city with a population of three million. He also had a summer house at Rivière-du-Loup, where the St. Lawrence River falls into the Atlantic Ocean, reaching a width of 25 kilometres and a depth of 30 metres. On both banks and on the island in its stream rise beautiful lighthouses. For years Michalak looked at these, even if only glancing at them through a window. He loved looking at them because, as he says, they symbolise to him all that is best about human beings: the desire to warn of danger, the desire to save in a disaster, the desire to bring help to survivors and the desire to point to a proper way of life. He had begun to visit Poland after the fall of communism, and when he set eyes on the lighthouse at Nowy Port, neglected and ruined but still preserving its former beauty, he told himself, “That’s for me! The lighthouse must be mine!” He already knew then that he wanted it not only to enjoy it himself, but to be able to make it available to all to visit. His project was greeted very kindly, favourably and positively with enthusiasm, both by the Gdańsk city authorities and by the Gdynia Maritime Bureau (Urząd Morski w Gdyni), which is responsible for the lighthouse. Arranging the formalities and then the repairs to the building lasted several years. The lighthouse underwent a thoroughgoing restoration, including exchanging the rusted parts of the railings on the viewing tower, putting in new oak windows and reconstructing the copper roof. During the renovation work effort was made to keep to the original appearance as closely as possible. Despite the fact that air pollution and natural atmospheric processes had done serious damage and many components had to be completely renewed, in each case reference was faithfully made to the building’s history. In so doing access was gained to some extremely interesting documents, such as the bill for the lens made in 1894 by Barbier & Fenestre of Paris, a lens which is still working at the top of the lighthouse.

So it was that on 7th May 2004, after a ceremonial opening, the Gdańsk Nowy Port Lighthouse began a new life as a historical monument to be visited and as a viewpoint from which the glorious panorama of the Trójmiasto and the Bay of Gdańsk may be admired. A total of 114 steps lead to the top of the lighthouse and during the summer visiting hours a light again burns at the very top. The building has also become a lighthouse museum in miniature. Among the objects on view are a telephone from the turn of the twentieth century, by means of which the Gdańsk lighthouse keeper could communicate with the port captain, a ship’s clock, that once struck what were known as “bells,” the signal to change the watch on board ship, and a nineteenth-century decorated Fahrenheit thermometer. Michalak could not pass over the pleasure of displaying a dozen or so beautiful lighthouses situated in his second homeland of Canada, and their great pictures adorn the interior walls of the building and may be admired, whether on arrival or on departure. In 2006 the lighthouse was entered on the national register of historical buildings and four years later Gdańsk Nowy Port Lighthouse received an award as a “well cared for historical building” in the Ministry of Culture and Heritage national competition.”

THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE TIME BALL

Another of Michalak’s dreams to be fulfilled is the return to the top of the lighthouse of an openwork time ball, the only one in the world. This success was achieved primarily thanks to Grzezgorz Szychlińki EngD, a distinguished specialist in tower clocks, who devised and completed this extraordinary project. The sponsors of the time ball were the firms Saur Neptun Gdańsk and the Port of Gdańsk Authority (Zarząd Morskiego Portu Gdańsk). In reconstructing the device Dr Szychliński made use of the original drawings of a German architect of the period. As a result of this, it was possible to recreate the dimensions of this unusual timepiece to within a centimetre of accuracy. The new construction is a faithful replica of its predecessor, although it has been made of high-quality stainless steel. The hoisting mechanism has been completely automated. The fall of the time ball marks punctually the hours of twelve noon and two, four and six in the afternoon according to the extremely accurate DCF77 time-keeping system created at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt in Braunschweig, which is transmitted on the 77.5 kHz long-wave band by the radio station at Mainflingen near Frankfurt-am-Main, a time-pattern whose precision has been defined as one second of acceptable accumulated error in 200,000 years!

The reconstructed time ball has a diameter of 1.6 metres and weighs 75 kilograms. When it remains in its resting position it is 36.5 metres above sea level (27.8 metres from the base of the lighthouse). In its cycle it travels 3.2 metres upwards in two stages and during its fall its mechanism begins to apply a brake just before the end of its course to weaken the impact on the (original) shock absorbers. With its time ball and mast the lighthouse measures 36 metres from its base. At twelve noon on 21st May 2008 a ceremonial inauguration took place and the time ball was demonstrated for the first time. During the summer season its fall four times daily is an unusual attraction, as there are only a few such time balls in operation in the world today. Most of them, it should be noted, reconstructed.